Seventy years after four Scottish students “liberated” the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey and took it back to Scotland, Michael Alexander examines the legacy which the ringleaders described as a symbolic show of national pride.

It was the day that four Scottish students removed the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey in London sparking a nationwide cat-and-mouse hunt which ended more than three months later when the stone turned up 500 miles away at the high altar of Arbroath Abbey.

On Christmas Day, 1950, Glasgow University students Ian Hamilton, Gavin Vernon, Kay Matheson and Alan Stuart “liberated” the ancient symbol of Scotland’s monarchy which had been used for centuries in the inauguration of its kings at Scone Palace.

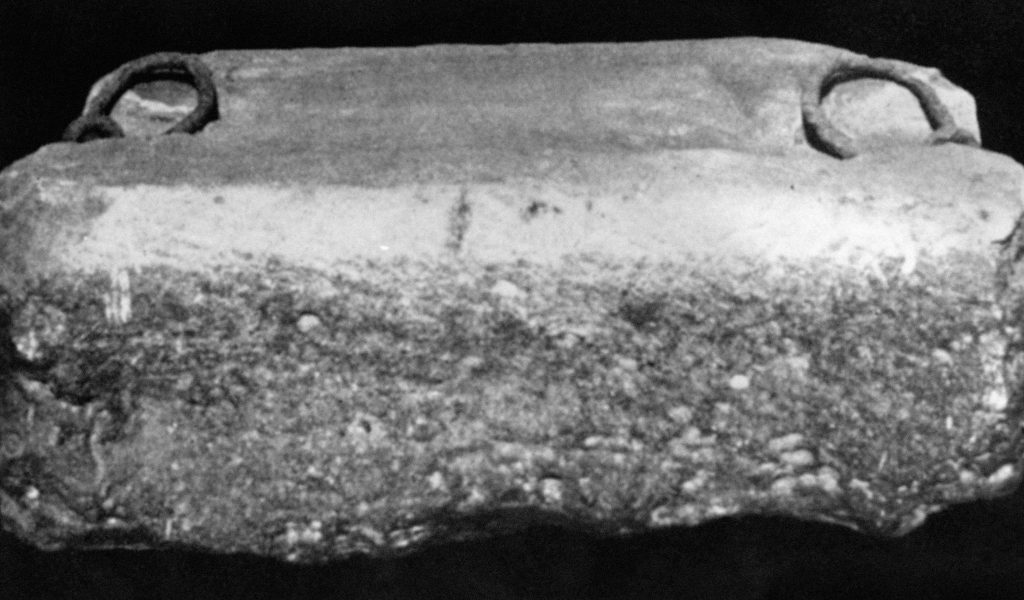

The Hammer of the Scots – King Edward I of England – seized the stone from Scone in 1296 and had it built into a new throne at Westminster.

From then on it was used in the coronation ceremonies of the monarchs of England and then Great Britain.

However, 34 years after the stone was officially returned to Scotland in 1996 for display with the Scottish Crown Jewels at Edinburgh Castle, and amid an ongoing campaign for the stone to be permanently displayed in Perth, the story of its infamous theft 70 years ago continues to intrigue.

Others, meanwhile, continue to doubt whether the stone now in Edinburgh is the real one at all!

How were the events of 1950 reported?

The events of Christmas Day 1950 were revealed in The Courier on Boxing Day when an article under the headline ‘Police Hunt Stone of Destiny Culprits: Watch kept on roads to Scotland’ told how a man and a woman “with Scottish accents” seen in the vicinity of Westminster Abbey in a Ford Anglia car early on Christmas Day may have been concerned in the removal of the Coronation Stone.

Acting on the theory that an attempt might be made to take the stone to Scotland, police set up road blocks on main roads towards Scotland and cars were stopped and searched.

The stone had last been seen in its place shortly after midnight. The loss was discovered about 6am by fireman Andy Hislop making his last rounds.

It was assumed those concerned attended the last service on Christmas Eve and at its close at 4.15pm, concealed themselves before the Abbey was locked.

On December 27 under the headline Land, Sea and Air Watch for Destiny Stone: Scotland Yard asks public to help, The Courier told how the country-wide search had been extended with police requests to seaports, airports, road transport drivers and railway employees to “aid in the watch for unusually heavy packages”.

It came as the Dean of Westminster accused the culprits of “committing an act of sacrilege”.

However, when an envelope was left on the counter of a Glasgow newspaper office on the night of December 29, containing two petitions to the king, the perpetrators promised to return the stone – if it stayed in Scotland.

The writers said they had removed the Coronation Stone and laid down certain conditions upon which it will be returned to official keeping.

One of the conditions was that the 150kg stone, which, it later emerged, broke in two after being dropped before being repaired, should be retained in Scotland in a place to be selected by the king.

The whereabouts of the stone remained a mystery for a further three months, however, until The Courier reported on April 12, 1951, that it had been left by three unknown men at the high altar of Arbroath Abbey, covered by a saltire.

The location was symbolically chosen as the place where the Declaration of Arbroath was signed in 1320.

At 1am the stone was taken from a Forfar police cell and carried by road to Glasgow before being returned to London.

It prompted Dr J MacCormick, chairman of the National Covenant Committee addressing St Andrews University Scottish Nationalist Society, to say: “The removal of the Stone of Destiny from Westminster and its return to public light in the Abbey of Arbroath has been symbolic of the determination of the new generation of Scots to insists on their national rights.

“Some deplore their methods, but no one can be blamed for their purpose.”

Liberation or theft?

Interviewed by The Courier in 2019, Ian Hamilton, now 95, who was ringleader of the famous Christmas Day Westminster operation, described his group’s capture of the Stone of Destiny in 1950 as a “liberation” not a theft, and looked back on the episode as a symbolic show of national pride that righted a 700-year-old wrong.

“I don’t consider that retrieving my country’s property was breaking the law,” said Mr Hamilton, a fervent nationalist who went on to spend more than 50 years as one of Scotland’s most respected QCs.

“After all, the Home Secretary said at the time that we would not be prosecuted.

“He referred to us as ‘these vulgar vandals’ and that has been one of my favourite phrases ever since!”

Mr Hamilton said he would be happy to see the ancient treasure returned to Perthshire, but would prefer to stay out of the on-going debate on its future home – so long as it stayed in Scotland.

Should the Stone of Destiny return ‘home’ to Perth?

The Courier is supporting the campaign for the artefact to move to Perth, to become the centrepiece of a new £23 million city centre museum.

Perth and Kinross Council launched its bid for the stone in 2016, claiming the iconic sandstone block could help bring in hundreds of thousands of new visitors to the Fair City.

There’s been a counter bid, however, to keep the stone in Edinburgh Castle.

Former Army officer and businessman John Bullough is at the forefront of a “once in a generation” campaign to bring the Stone of Destiny home to Perth.

As chairman of Perth City Development Board from its formation in 2012 until earlier this year, he believes the Stone of Destiny has the potential to “single-handedly change the future” of Perth city centre.

“Anybody that has visited the stone in its inaccessible, dark and claustrophobic room at the back of Edinburgh Castle, could only conclude that it does not form an essential part of the castle’s collection,” he told The Courier.

“As Scotland’s greatest artefact, one of world’s most iconic symbols of national identity, the Stone of Destiny’s story is steeped in romance, intrigue and violence, and is inseparable from our pride as a historic sovereign and once independent nation.

“Perth’s exciting plans for a new £30m museum with the stone as it centrepiece, telling the story of Scotland’s birth as a nation, will rectify this travesty, make Perth an essential destination for foreign and domestic tourism and act as a catalyst for the regeneration of our city centre.

“Our bid to relocate the stone and make the Stone of Destiny synonymous with Perth’s identity has huge advantages not just for the Fair City, but for the whole of Scotland.

“Crucially it would be free to visit; Scots should not have to pay £19 to see their own coronation stone.

“Furthermore, Perth’s unique location provides access in 90 minutes for circa 4m of Scotland’s population.

“The stone would also be in the correct historical context, only two miles from its original home at Scone Abbey (now demolished), where Scone Palace now stands.

“External studies show that up to 280,000 extra visitors a year would visit Perth by 2024, transforming our struggling High Street and becoming a beacon for the regeneration of our city region.

“But it’s not all about Perth city centre.

“There would be significant spin-off benefits for communities across the whole region; creating new jobs, traineeships and apprenticeships that would build GVA and boost the whole county’s economy.”

Not everyone, however, believes the stone currently housed in Edinburgh Castle is the real deal.

Amongst them is Scone Palace head gardener and BBC Beechgrove Gardener presenter Brian Cunningham who believes the original stone is buried in the foundations of Scone Palace.

Was the original stone hidden in 1296?

Legend has it that in 1296, the monks of Scone Abbey duped the English monarch with a fake, under torture, and that the ‘real’ stone, reputed to have been used as a pillow by Jacob in biblical times, was hidden where it also still remains.

“Do I think the Stone at Edinburgh is the real one? No!” said former St Andrean Brian, who also writes the Ginger Gairdner gardening column for The Courier’s Weekend Magazine.

“Apparently after King Edward raided Scone for the stone he actually sent armies back a further two times, clearly thinking the monks had duped him.

“I’ve heard stories that the real stone is hidden in a dyke in a village up the road and another saying that the stone is buried somewhere on Scone island.

“Personally I think it is part of the foundations of the palace, hidden in there somewhere.

“I’m sure Lord Mansfield knows but every time I see him he just says that he’s not going to tell me!”

Brian said getting the Stone of Destiny (or at least the ‘fake’ one!) up to Perth would “just be massive for the city and for Scone Palace” –especially with the economic fallout from Covid.

“Hopefully people would stay and take advantage of the hospitality we have,” he said, “but what a day that would be for the tourist – into Perth to see the stone and learn about its history then a trip out to Scone Palace to see the grounds where all this history took place.

“Especially Moot Hill where the Kings of Scotland were crowned.

“I’m sure Edinburgh has quite a few other/enough historic attractions for tourists. The stone has a strong connection with this part of Scotland. It seems a natural place for it to be with the benefits to the area it would be bring.”

Do the Knights Templar have the ‘real’ stone?

It’s not the first time there’s been speculation about the whereabouts of the ‘real’ stone.

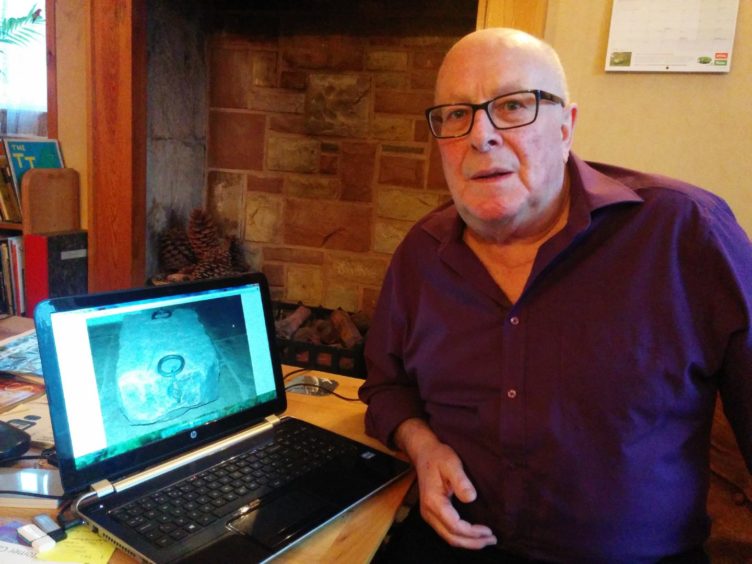

In 2016, two Courier Country men spoke exclusively for the first time about their role in the secretion of what many believe is the ‘real’ stone, which, they understood, is still hidden at a secret location somewhere in Scotland.

Charles Henderson, then 72, a retired engineer of Auchtermuchty, was working his way around Scotland photographing castles in the early 1990s when he made friends with David Eaton, then 73, of Meigle, who was at that time, custodian of Dunfermline Abbey.

In 1991, Charles was asked by David, who was a chevalier with the Knights Templar, if he would help him move the ‘real’ Stone of Destiny from the now demolished St Columba’s Church in Dundee.

The stone, locked inside an iron cage, had been on display in the Lochee church since 1972 under the care of the Rev Dr John MacKay Nimmo.

A Scottish nationalist organisation, the 1320 Club, claimed it was the genuine stone stolen from Westminster Abbey by four students in 1950 and never returned.

The stone returned to Westminster was a replica, made by a Glasgow stonemason, the club claimed – although the abbey always said it was sure the stone in London was genuine.

Charles said he was then asked to drive it to Hatton Castle, Newtyle.

A few months later he was asked to pick it up again and move it on to a former church, bought by the Knights Templar, at Dull near Aberfeldy, Perthshire, where more photographs were taken with Knights Templar in full regalia.

He understands the stone was later moved to Logie Coldstone, Aberdeenshire – but he “lost track after that”.

Mr Eaton, who said he was no longer involved with the Knights Templar, said he too remained “open minded” as to whether they moved the ‘real’ Stone of Destiny.

Historic Environment Scotland, said at the time: “We are confident that the Stone of Destiny on public display at Edinburgh Castle is the stone that was taken to Westminster Abbey by Edward l in 1296.”

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for The Grand Priory of Knights Templar in Scotland said that Bailey Gray – the stonemason who hid, and repaired, the Westminster stone when it was stolen in 1950 – used a fake in his shop window as a publicity stunt.

Once the Westminster Stone was recovered the fake disappeared but re-appeared in Parliament Square in Edinburgh in 1972.

The Rev John Nimmo took ownership of the stone until his Dundee Lochee Church closed and then the stone was moved to a Scottish Knight Templar Church at Dull, Aberfeldy.

On the sale of this church the fake stone was moved around the country and its current whereabouts were “unknown”.

It’s been suggested the ‘real’ stone of Scone, from before 1296, was probably black in colour.

But that stone has never been found!