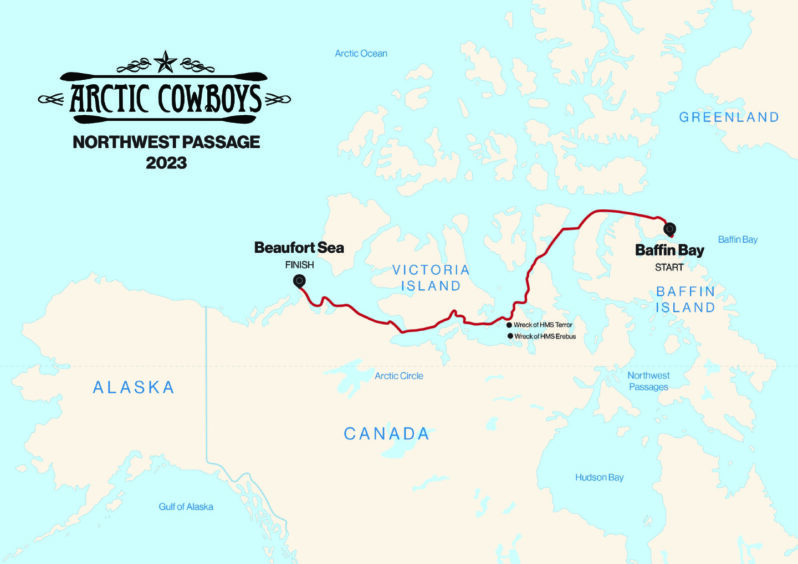

When record-breaking adventure sports journalist and author Mark Agnew set out with a small team aiming to be the first to kayak the entire 2,000-mile Northwest Passage, from Baffin Bay to Beaufort Sea last summer, he couldn’t help but think of the Dundee whalers who were making a living in the High Arctic a century and more ago.

The fabled maritime route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic has long captured the imagination of explorers, traders and nations.

Mark’s journey was only possible as the ice is retreating for longer each year.

Over 83 days, the team of four kayaked for 12 hours a day, camping on the shore each night and hunkering down in their tents to sit out storms.

Overcoming 15 feet waves and sea ice, and evading polar bears, they set two world records for being the first to kayak the Northwest Passage and the first to complete the entire route under human power.

However, ahead of Mark giving a talk to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in Kirkcaldy about his travels, the 32-year-old has told The Courier how childhood camping trips to Loch Tay in Perthshire “planted the seed” of adventure that drove him on to bigger things.

“My parents really got me into adventures and the outdoors,” explains Mark, who was also inspired by his former explorer father Crispin – an honorary research fellow at Dundee University’s law school – who mapped part of Greenland, was the first person to walk north to south across the Patagonia ice cap, and led expeditions to Antarctica and the Himalayas.

“We were always camping and on holidays we’d go up by Loch Tay and go hiking and sailing and stuff like that.

“I can’t remember if we went kayaking.

“We certainly rented these paddle board bicycle things.

“You sat on a paddle board with these pedals. That was something we enjoyed.

“I went kayaking when I was very young with my dad around Skye.

“That planted the seed.

“But Loch Tay was also important later because one of the first Munros I did by myself – without my dad – was Ben Lawers.

“I came up with some friends in winter.

“While it was a well-trodden path, I had to think about planning and look at weather and stuff like that.

“I look back at that and think ‘yeah, we did that on our own’.

“That was one of many stepping stones to bigger things.”

Why did Mark Agnew decide to kayak the fabled Northwest Passage?

Growing up in Edinburgh, Mark, who attended Fettes College, studied politics and sociology at Newcastle University.

After graduation, he moved to Hong Kong for eight years where he worked as a journalist on magazines.

He “super charged” his journey towards becoming an adventurer when he became the adventure sports editor for the South China Morning Post.

He began to take adventure more seriously.

However, his first major expeditions did not go to plan.

In his 20s, Mark was rescued from the Atlantic in a bid to set the world record for rowing from the Canary Islands to the Caribbean.

He was rescued again attempting the same feat two years later.

The failures hit Mark hard.

“The first one I was part of a pay per place group and it went very badly,” he recalls.

“We lasted 48 hours before we were picked up by helicopter. It led to headlines like ‘Captain Calamity’.

“The second one was part of the annual race called the Talisker Whisky Atlantic Challenge.

“It failed for technical reasons. But that one really cut me deep because the first one was so obvious we had to get off. The second one was like ambiguous. Are these technical problems big enough for me to get off or should I go on?

“I still don’t know what the right decision was, but certainly for a long time afterwards I was convinced I’d made the wrong decision.

“I absolutely loathed myself for quitting and giving up. I just thought I was utterly pathetic.”

Mark Agnew had to find new confidence before taking on the Northwest Passage

Mark was forced into a period of introspection, wondering what he really wanted out of adventure.

In a bid to rebuild his mental strength, he began to push himself beyond his limits.

He ran countless ultra-marathons, including the notorious Hong Kong 100km, with over 5,000m of cumulative elevation gain.

He rowed around Hong Kong Island and spent days kayaking from remote island to remote island, living out of a tent.

The adventures gave Mark an immense reservoir of resilience and faith in his own ability to push and survive in the wild.

With his newfound – or re-found – confidence, he began to dream of bigger things.

The Northwest Passage had long held sway over his imagination.

Growing up, he was aware the quest for the Northwest Passage dated back centuries.

Early explorers sought a shorter route to Asia for trade purposes.

Icons like Sir John Franklin and Sir Martin Frobisher embarked on perilous journeys through icy waters, facing treacherous conditions and often tragic outcomes.

The allure of a navigable passage through the Arctic archipelago persisted despite initial failures.

However, he’d also learned from his experiences that he should focus on the intrinsic value of adventure itself, and not necessarily just the destination.

What were main challenges on Northwest Passage kayaking adventure?

Setting off in tandem kayaks on July 2 from Baffin Bay, Greenland, with three Americans – expedition leader West Hansen, Jeff Wueste and Eileen Visser – Mark said every single day was tough for the so-called ‘Arctic Cowboys’.

He’d prepared himself for “monotony”.

During training, he once took out a rowing boat and went back and forwards over 3km for 12 hours straight in the dark from 8pm until 8am to try and get his mind used to being bored.

But what surprised him was how varied the challenges were.

“The first challenge was sea ice,” he says.

“The ice is melting but it’s not gone.

“Even ice-free means an area of sea that has 15% ice concentration or less.

“That was difficult. We started and immediately got turned around by the ice.

“We spent two weeks in a basic wooden little shack waiting for the ice to move again.

“Then we pushed on finally after two weeks and got trapped in the ice again.

“It just kept on happening and that was just a massive challenge and dangerous and we really didn’t know how to deal with the ice and what to do except to wait it out.

“Then the middle third – it was just barren, flat land.

“There was no running water.

“We were drinking puddles and stuff, and it was all about chewing up the miles to try and make up time being lost in the ice.

“The final bit, we just knew winter was coming so we just had that hanging over our heads.

“We just turned on the speed in a way that we hadn’t until then. We were doing 30, 35, 40 miles a day. It took its toll. I became so hungry.

“Then with still 100 miles to go, winter did arrive. It got really brutal. The cold was awful.

“The fresh water was all frozen.

“Eileen and I once walked for hours to try and find some unfrozen water to drink.

“Then we had to break through with an axe and scoop out from a puddle again.

“The challenges changed over time – it was very varied.”

How cold and wet did Mark Agnew get kayaking the Northwest Passage?

Mark said that during the early stages of the adventure, temperatures were “surprisingly warm” – sometimes around 10C.

In his tent, he’d wear shorts in his sleeping bag. He had flip flops.

When kayaking in a dry suit, it also got very warm.

Yet by the end in October, it was well below freezing by day and night.

Mark said one of the ways the trip opened his eyes is the way that climate change manifests itself.

“Ignorantly”, he says, he previously assumed that the ice disappearing meant that the ice is melting more and earlier each year.

But an Inuit told him their experience is different.

It’s just become “completely unpredictable”.

“They used to say when they were younger they could go fishing from this date onwards,” says Mark.

“But now it’s sometimes four weeks earlier or it’s four weeks later.

“That makes it impossible for them to plan.

“Secondly, everybody’s talked about how dry it was up there. It never rains. It’s so cold that the air can’t hold the humidity.

“By the end of the summer it was raining and we got soaked. It was too cold to dry, so we just stayed wet.

“My socks were wet, my sleeping bag was wet, everything I was wearing was wet.

“It’s things like that you just don’t think about.

“You think it’s getting warmer and the ice is disappearing.

“But it’s just unpredictable and changing in different ways. It’s not just simple and linear.”

What are the implications of the Arctic becoming more accessible?

Mark says it’s also made him realise that because the ice is melting it’s making the Arctic more accessible.

As well as wildlife, they saw lots of things like NATO fuel tanks, early warning detection towers pointed towards Russia, massive Coastguard ships, and cruise ships embarking on “climate change tourism”.

“There’s a lot of tensions up there about different countries claiming different areas,” he adds.

“From an environmental and political impact they are all interlinked.

“It opened my eyes up to the way climate change is manifesting itself beyond the simple metric of ‘it’s getting warmer’.”

Reflecting on the history of exploration of the area, Mark is proud to be a Scotsman.

While conscious of some of the more negative aspects of historic trading on indigenous peoples, around 90% of the Hudson’s Bay Company employees were from Scotland.

The kayakers spent a few days in a cabin called Fort Ross, which is the last Hudson Bay cabin that exists.

Mark laughs that he’d have taken his bagpipes with him if he’d had space.

Does Mark Agnew have other kayaking adventures planned?

While he doesn’t have other adventures planned in the immediate future, training for the Northwest Passage also helped him realise that the UK is not just a training ground – it’s an adventure place in itself.

“When the Northwest Passage trip was delayed in 2022/23, I went on an adventure and kayaked down the west coast of Scotland from Plockton near Skye to Arisaig, and as I passed Munros, I pulled up onshore and hiked,” he smiles.

“I also went kayaking around the Bass Rock (in the Firth of Forth), which is a short day trip but really, really incredible.

“The UK and Scotland in particular – it matches anything anywhere else has to offer. It’s just phenomenal.

“And now I’m back from the Northwest Passage, people always ask me ‘what’s next’?

“They seem disappointed because I now say I’m really motivated to do adventures in the UK – particularly Scotland – because I spent so long dreaming of the distant corners of the world that I forgot what was under my nose.

“They think I’m downgrading.

“But if you kayak the whole way around the UK, that’s further than the Northwest Passage.

“On what metric is that not as adventurous?

“You could do a lifetime in Scotland and still have things to do.”

Mark Agnew: Exploring Motivations in the Northwest Passage for the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, February 19, at 7.30pm, The Old Kirk, 40 Kirkwynd, Kirkcaldy, KY1 1EH.

Conversation