Alexander Selkirk, widely regarded as the ‘real-life’ Robinson Crusoe, died 300 years ago on December 13. Gayle Ritchie celebrates the life and legacy of the marooned Fife-born mariner – and asks why more isn’t made of the historic famous link.

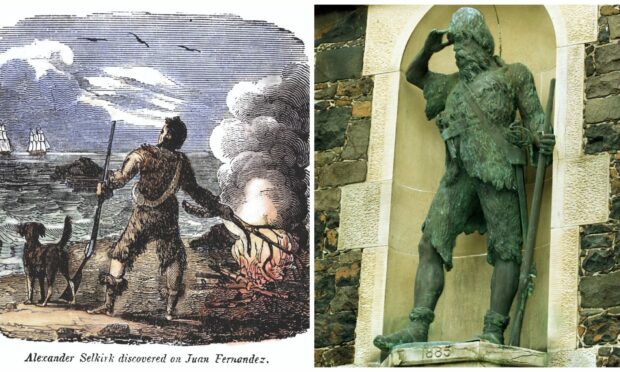

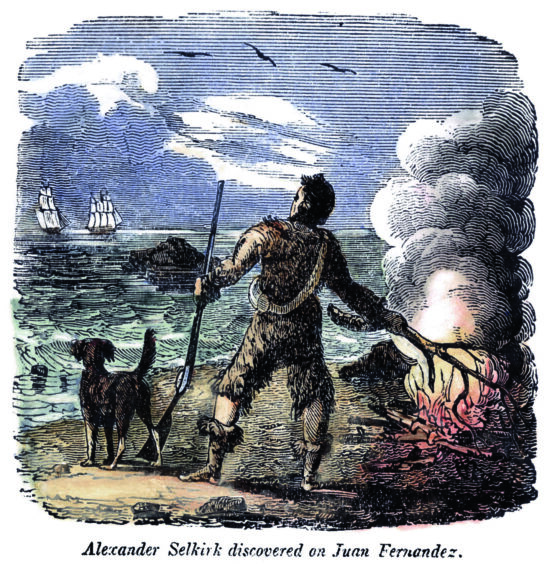

He is the stereotype of the desert-island castaway – dressed in furs, clasping a musket, sporting an unruly beard and gazing out to sea in hope of being rescued by a passing ship.

The story of Robinson Crusoe is well known, but how many people are aware that Alexander Selkirk, a sailor from Lower Largo, was the inspiration for the fictional character?

Indeed, less informed visitors who stumble on the statue of Selkirk, erected in the Fife village in 1885, presume it is of Crusoe himself.

A glance online and you’ll find references galore to the “Robinson Crusoe statue” of Lower Largo, and a signpost (pointing the way to the “Robinson Crusoe statue”) in the village serves only to further perpetuate the confusion.

Many people believe that if it hadn’t been for Selkirk, there might never have been a Crusoe; the shipwrecked protagonist might not have been invented.

As December 13 marks the 300th anniversary of Selkirk’s death, it seems fitting to celebrate this “soiled and wayward” mariner from Fife.

Marooned mariner

The son of a cobbler, Selkirk was born in Lower Largo in 1676 and his rebellious nature – he’s been described as a “hothead, a pirate and a lout” – got him into trouble with church authorities as a young man. He was drawn to a life at sea where he was engaged in buccaneering in the Caribbean before joining an expedition of privateers – pretty much pirates licensed by the Crown – to the South Pacific.

In September 1704 his ship, the Cinque Ports, moored at an island in the Juan Fernandez archipelago, then known as Mas a Tierra (now Robinson Crusoe Island), 416 miles off the coast of Chile.

Selkirk voiced grave concerns about the vessel’s seaworthiness and told captain Thomas Stradling if repairs weren’t made he would stay on the island.

Stradling set off without him, leaving him with a musket, hatchet, knife, cooking pot, bedding, clothes and bible.

It turned out to be a blessing in disguise as the ship sank with the few survivors captured and imprisoned.

Realising rescue wasn’t going to come quickly, Selkirk fought to adapt to island life, struggling with loneliness and depression and attacked by ravenous rats at night.

He survived by eating lobster, feral goats, berries and wild vegetables and living near feral cats. He proved resourceful, building two huts and fashioning various tools.

Four years and four months after being marooned, on February 1 1709, two British privateers dropped anchor offshore, and on spotting Selkirk’s signal fire, they approached to discover a “wildman” dressed in goat skins.

Back on British soil, Selkirk published an account of his adventures, causing great excitement.

He re-embarked on his career as a privateer and within a year was master of the ship that rescued him. In 1712 he returned to Scotland a wealthy man with all his looted goods. He surprised his family in Largo who had long given him up for dead.

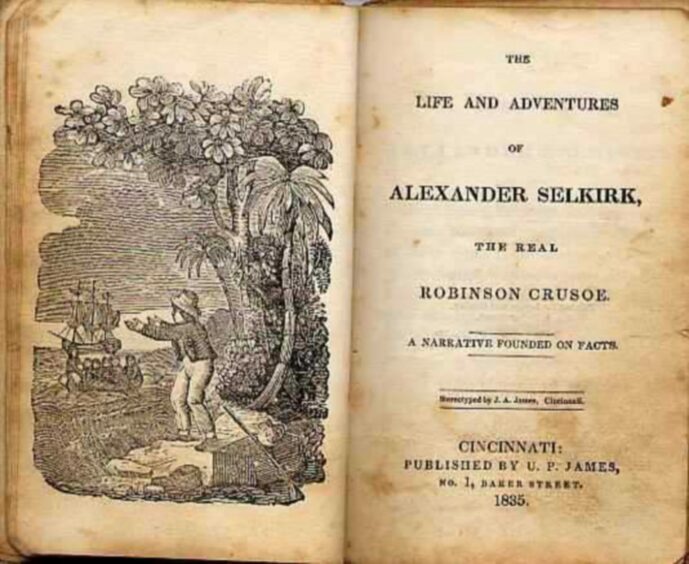

Selkirk’s stories are regarded by many as the main source of inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe, published in 1719.

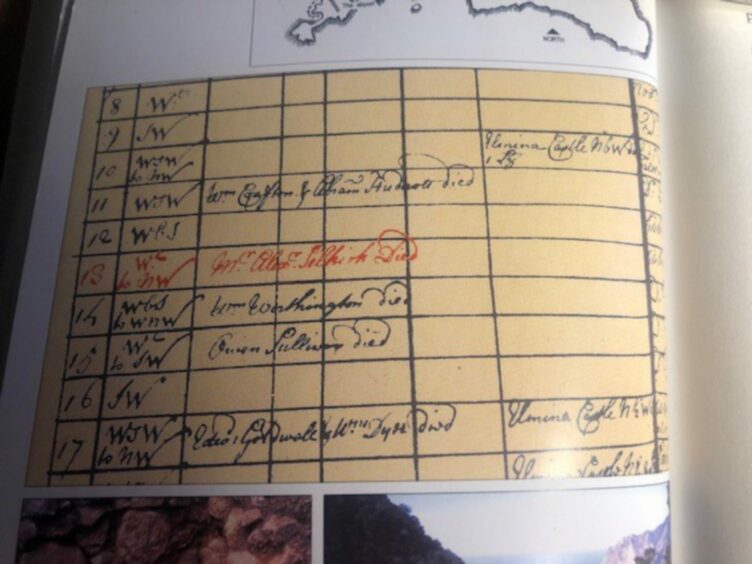

Two years after publication, on December 13 1721 and at the age of 45, Selkirk died of yellow fever.

‘His life, if not his death, should be celebrated’

Edinburgh-based author and journalist Rick Wilson believes Selkirk’s birth village of Lower Largo “seriously undersells itself”.

“I have seen many tourists, mainly Japanese and American, seeking out the house that replaced his birth home – with its magnificent statue – and being disappointed with the lack of maintenance and general celebration of the unique connection,” says Rick, author of The Man Who Was Robinson Crusoe: A Personal View of Alexander Selkirk.

“If this were America, there would be big signs and themed shops all over the place… not to mention Crusoe burgers for sale. We don’t need all that of course, but we do need a bit more pride in the place.

“We should be delighted that Graham and Rachel Bucknall have taken over and reopened the village’s Selkirk-themed Crusoe Hotel in July. “They of all people will know how to make it a real landmark tourist attraction.”

‘Not a shining good-guy hero’

Selkirk was alive to see Crusoe become an instant best-seller and must have known, more than anybody, what his input to the story had been, reasons Rick.

“After being rescued from the shores of rugged Juan Fernandez, he came home a rich man from a later privateering expedition that captured some treasure ships,” he says.

“He tried to resume his family life in Largo but got bored and joined the Navy. His life story ended by his succumbing to a virulent tropical disease onboard HMS Weymouth on December 13 1721.

“He was not a shining good-guy hero but he was a great navigator and his life was very colourful, with the world at his feet and two women claiming his money and Largo property.

“He was also a proud, albeit bad-tempered, Scot who left a great story for us all… even if it was just his own unalloyed one. As such, his life, if not his death, should be celebrated.”

Rick says anyone who expects Defoe’s Crusoe story to “slavishly” reflect Selkirk’s experience – marooned for four and a half years as opposed to the fictional hero’s 28 – will be disappointed.

But while the tales may be different, they are – in Rick’s opinion – as good as each other.

“Many of the details of the experience surely come straight from Selkirk. Particularly the dressing up in goatskins which gives a lasting image of both characters. Selkirk may not have been Defoe’s main source (which was his imagination) but was surely his main inspiration.

“I have no doubt Defoe milked Selkirk for all he was worth, as both men lived close to each other in Bristol after Selkirk’s return.

“Indeed, they are said to have drunk together in the still-extant Llandoger Trow pub (which boasts of the meetings) and I learned from a local historian that they definitely met several times, socially in a private home, during which Selkirk was seen to hand over ‘some of his papers’ to Defoe. Imagine what these would be worth today! The original notes of the world’s best-selling story. Ever.”

Rick says Selkirk’s English wife believed the notes had been given to the Duke of Hamilton but, despite writing to him with a claim, she failed to get her hands on them.

“Personally, I have no doubt that with his journalist hat on Defoe interviewed and borrowed liberally from the Scot, whose accent he would have well understood, having been once an English spy in Edinburgh at the time of the Union,” he says.

Why, after 300 years of “bestsellerdom”, is the Crusoe/Selkirk tale still so compelling?

Rick reckons it’s because it’s a story that fascinates us all, wondering how we would cope with the challenges of being marooned alone on a desert island.

“It still works as a theme,” he adds. “See Tom Hanks in Cast Away and the evergreen appeal of Radio Four’s Desert Island Discs.”

Adventurous forebear

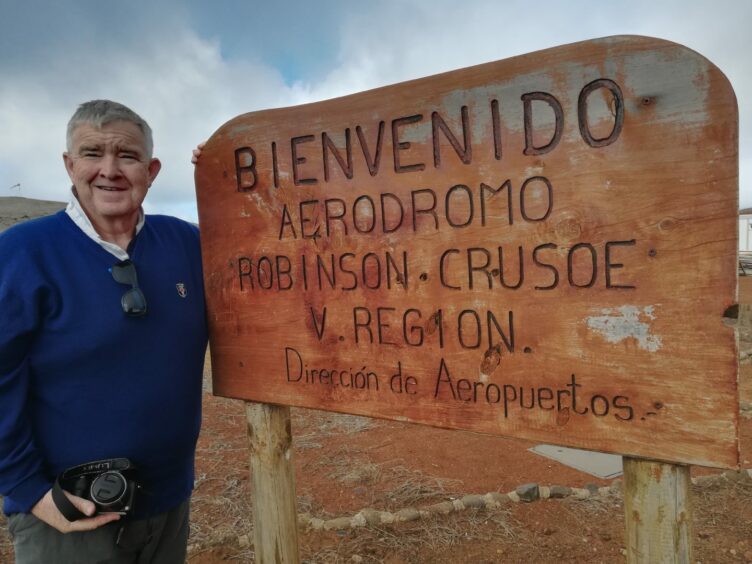

In April 2019, 300 years after the publication of Robinson Crusoe, Ian Hendrie fulfilled a lifelong ambition to visit Robinson Crusoe Island and walked in the footsteps of Selkirk, his great uncle nine times removed.

Ian, 61, who recently moved from London to Lundin Links, was treated like a celebrity by residents of tiny Isla Más Afuera, which was renamed as Alejandro Selkirk Island by the Chilean government in 1966.

He and his wife Stephie made the trip from Santiago while visiting daughter Eloise on an internship.

They flew on a small plane to the island’s tiny airstrip then travelled by boat to the main town.

When Ian showed his host a slip of paper showing his family tree, the proverbial red carpet was laid out.

He was taken to the spot where Selkirk built his home and introduced to people eager to meet the descendant of their hero.

He also spoke to schoolchildren and attended a Selkirk-themed conference.

“I explained why we were there, that we were from Lundin Links next to Lower Largo where there is a plaque for Selkirk and a statue,” he recalls.

“We were treated like absolutely royalty. The mayor gave me a certificate for my visit and lots of photographs were taken.”

While Ian believes most people regard Crusoe’s story as “fiction”, he thinks the people of Robinson Crusoe Island could benefit from more publicity.

“Life is hard there and it certainly doesn’t benefit from tourist numbers due to its remoteness. That makes it special. But there must be a worry that in time youngsters will leave and they’ll end up with a sort of St Kilda in the Pacific.”

Former retail banker Ian, who describes his ancestor as a “rascal” who stood up to authority, says he’s “very proud” of Selkirk.

“The story of Selkirk was always a big family story. One of my mum’s aunts had the family tree drawn up and coming to Lundin Links and Largo for our annual holidays reinforced the connection every year.”

Ian’s family will paying their respects to Selkirk on the 300th anniversary of his death in their own quiet way.

“We don’t have anything specific planned but we think it would be a good idea to create a ‘Crusoe Zone’ in Lower Largo for visitors.

“The statue on Main Street is iconic but it stands alone.

“We have signs to steer visitors but you probably have to be of an age to know of Robinson Crusoe or indeed Alexander Selkirk.

“Various people think some sort of ‘centre’ or information board would be a good idea in Largo.

“There are several possible locations and I’m sure QR codes could release information and even raise funds for the island. Maybe some of the artefacts from the museum in Edinburgh could be shown locally.”

Ian says the mayor and his wife from Robinson Crusoe Island visited Largo in 2017, enjoyed a drink at the Crusoe Hotel and left a signed book, “but there is no record of the visit or indeed the gift to the village”.

A second trip to Robinson Crusoe could be on the cards for Ian – if he can convince Stephie to travel 30 hours in a supply boat.

He laughs: “Can you imagine seeing the island appear over the horizon just as Uncle Sandy did all those years ago!”

Cartoonist

When illustrator and designer Allan Jardine, a descendent of Selkirk – “he’s nine times my great uncle” – asked around locally to see if there were any plans to commemorate his ancestor’s death, he was disappointed to discover few people were interested.

“We might not have the story of Robinson Crusoe if it weren’t for Alexander Selkirk, so he’s well worth celebrating,” says Allan.

“The story seems to be the other way round though – a lot of people seem confused about it.

“My family put up his statue (in 1885) and paid for it.

“My visit to Juan Fernandez Island in 1983 was on page three of the Chilean newspapers while Margaret Thatcher’s trip to the Falklands was on page five – so Selkirk was big news there.”

As a child growing up in Largo, Allan was brought up knowing about Selkirk and loved hanging out near the “imposing statue”.

He’s sad there’s not the “same feeling” for his ancestor as there was in the past.

“Maybe people don’t care so much about local people on their doorstep which is strange! Some might view Selkirk as a drunken sailor stuck on an island but it wasn’t his fault. He feared the ship would sink, and it did! He was eventually rescued while those on the ship were jailed, so he got the better deal really. But people don’t seem to be aware of the significance of the man.”

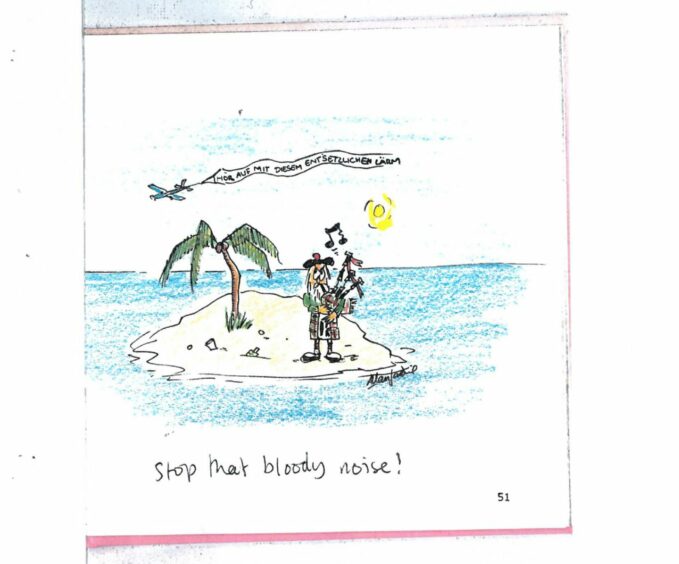

Allan, a studio technician at Edinburgh College of Art, was commissioned to create a book of “island cartoons” by Farhad Vladi in 2000.

“He buys and sells islands and asked me to do this after he found out my connection to Selkirk and that I was an artist.

“The idea was that he could give them as gifts to his clients. We’ve been friends since and have appeared talking on TV shows and at press events, with him talking about his island business and me about my ancestor Alexander.”

Soiled and wayward

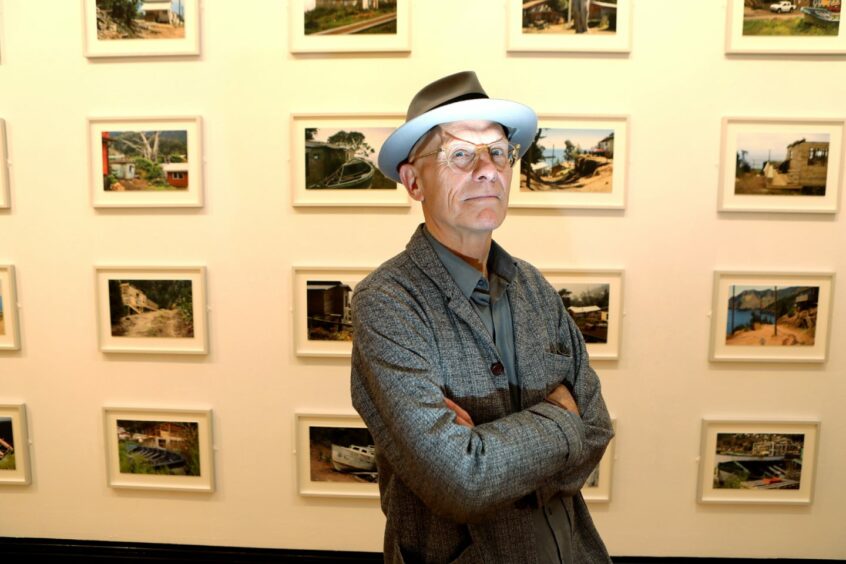

In 2019, 300 years after the publication of Robinson Crusoe, Glasgow-based artist Roger Palmer exhibited a series of Selkirk/Crusoe inspired photographs and illustrations at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Titled REFUGIO, the exhibition explored the blurring of fact with fiction between Selkirk and Crusoe.

Aware Selkirk had been once been described as “soiled and wayward” by 1829 biographer John Howells, Roger felt this was no reason to airbrush the sailor out of the Crusoe story.

David Caldwell, a retired National Museums Scotland executive, held a similar view, saying: “Selkirk’s contribution has long been under-recognised but I fear it’s getting worse. A recent radio programme discussed the authenticity of Robinson Crusoe without once mentioning the sailor from Lower Largo.”

It’s refreshing, therefore, to hear new Crusoe Hotel owner Graham Bucknall claim Selkirk is very much on his radar: “Customers look out at the same waters as Selkirk did when he sailed off on his life-changing journey,” he notes.

“Selkirk made a huge impact on literature and inspired Defoe to write Crusoe. He’s a trope for a man alone on a desert island and his is a story that people should know better. We won’t be laying on Crusoe burgers but Selkirk is here in our psyche. His story should be celebrated, as should the stories of many great Scots setting sail on expeditions.”