The darkness, and the enemies concealed there, press closer, the walls of the tunnel tighten, and beneath the jungles of Vietnam, John Keaveney feels a long way from home.

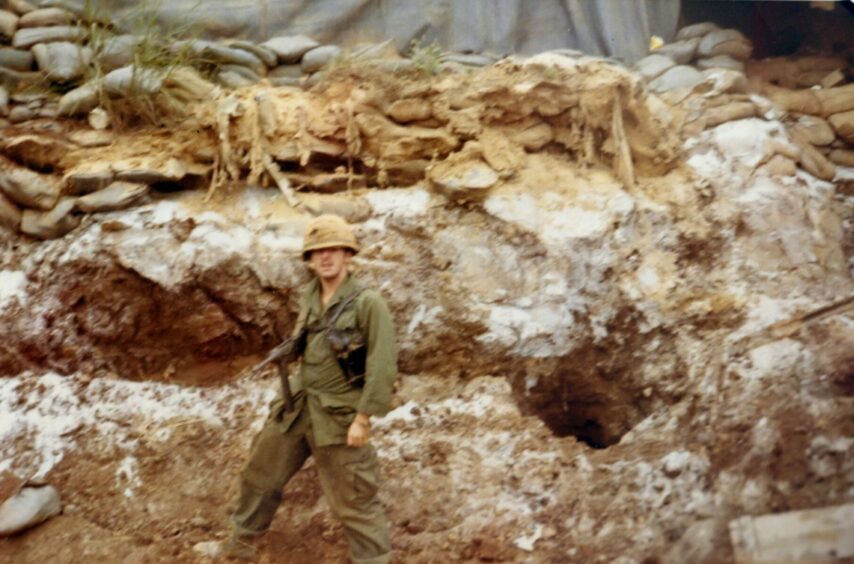

The teenager had enlisted in the US Army soon after leaving Scotland and, at five foot four and weighing just eight-and-a-half stone, he volunteered as a tunnel rat in the South East Asian conflict, pursuing Viet Cong insurgents into subterranean labyrinths stretching for miles.

Young Keaveney was typical of the small – in number and stature – band of brothers taking the war beneath ground as they inched through the tiny, claustrophobic tunnels, often measuring just two feet by three, where danger could lurk just beyond the torch’s beam.

The veteran, who was later seriously injured in a mortar attack, says: “We couldn’t take big weapons down in the tunnels, all we had was a 45 pistol, a knife and a flashlight. If I shot my 45 in the tunnel, the flash would blind me and the noise would deafen me. The only thing I could do is stick my knife in the enemy. I wasn’t willing to do that on a daily basis.

“I’m not brave, I’m Scottish,” he adds with a smile, “but I still get nightmares. Not as many as I used to though.”

His service in Vietnam took a terrible toll, as, in the years ahead, he endured post-traumatic stress disorder and what he believes is the legacy of toxic herbicide Agent Orange, which was used by the Americans to destroy forest and crops.

Now, on Tuesday, more than half a century after leaving, Keaveney, 72, will return to Scotland. He says: “I am an old soldier coming home to die.”

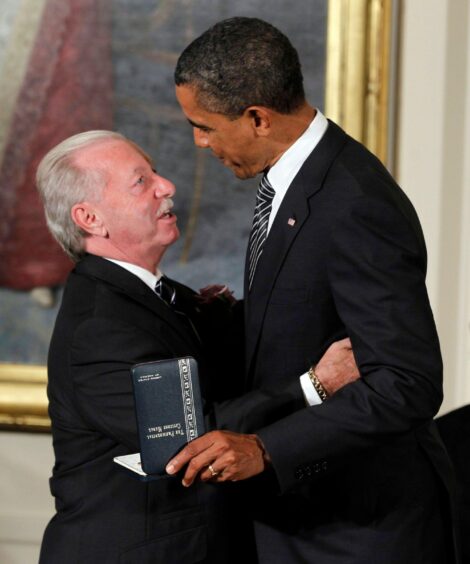

Before leaving his home in Las Vegas, Keaveney charted his extraordinary life, which took him from the gangs of Glasgow’s East End, and the tunnels of Vietnam, to prison, redemption and on to the White House. After leaving the US Army, tormented by what he saw on two tours of duty in Vietnam, he plunged into addiction and crime, before turning his life around, taking charge of the New Directions charity to help shattered veterans like him find a foothold in civilian life.

His work was recognised in 2011 when he was presented with America’s second-highest civilian honour, the Presidential Citizens Medal, by President Barack Obama. Eight years earlier, he had been awarded a Bafta Los Angeles Britannia Award after his work with veterans had been highlighted by Tom Hanks, a supporter since starring in Saving Private Ryan and co-creating HBO’s Band Of Brothers with Steven Spielberg.

It all seemed a long way from the jungles of Vietnam but even further from Glasgow, where he was born illegitimately and raised by his grandparents in Bridgeton. He was 15 when he fell in with the Spur gang and was involved in a horrific knifing incident with a Calton Tong rival. His uncle, head of the Glasgow seaman’s union, sent him to seaman’s school in England before he began a three-year career in the Merchant Navy. He recalls: “My uncle told me not to come back. I was twice around the world before I was 16, but I jumped ship in Veracruz, Mexico, and came across the border into America to another uncle who was living in Santa Monica.”

An illegal immigrant, he was just 18 when he enlisted for the army and the war in Vietnam in 1969, becoming a US citizen in the process. He had two tours of duty, 1969-70 and 1971-72, but admits he was not prepared for the horror and simply describes his first post on the North-South Vietnam border at Con Thien, the “Hill of Angels”, as hell on earth.

Keaveney was part of an elite band of 700 so-called tunnel rats chosen out of an entire fighting force of 2.7 million. His job was to flush out Vietcong fighters from the vast underground burrows and chambers, often facing deadly hand-to-hand combat.

Reliving that time, he says: “I got a job as a soldier and was quite happy at it. But when I went to Vietnam the reality of it, what they teach you and what is real, set in pretty quickly when you’re forced to engage in the doom of combat.

“Con Thien was like being on the moon. You couldn’t go further north. It was a highly contested area with a lot of combat. The 1st Marine Division was there. We went in by helicopter. Con Thien was my rear base and we would go out on missions from there.”

He saw many comrades die but not close friends – only because he made a conscious choice not to form tight bonds. “You don’t want to be too close to people,” he explains. “You don’t want to feel that kind of hurt. It’s not the kind of thing you want to deal with. My head was in a bad place because of all the combat I’d seen. They took me out of the field a month before I got wounded because they wanted to check me out. The reason for that was because I had a specific job to do.

“Because I am small, and when I was young weighed only 118lbs, I could crawl into these holes. They called me a tunnel rat. I went in after the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong. When bunkers were found, someone had to go down there and find out if they were hot or cold (ie whether the enemy were inside).

“They knew I was in the tunnels and I knew they were in the tunnels. They were wily little guys and they could fight too. I still get nightmares, that I am down in a tunnel but not as much as I used to.”

When he was eventually wounded it was the result of a mortar attack. He recalls: “I was riding on top of an armoured personnel carrier with my squad, going to Khe Sanh when the enemy dropped mortars into us.

“They hit just in front of the vehicle. All I remember was a floating sensation and my mouth being really dry. I couldn’t see out of one eye and I couldn’t move. I found out later that some of the other guys on the track we had been riding in front of were killed.

“So they loaded us into the helicopter and threw the equipment in on top. I couldn’t move because the dead were on top of me. I was so thirsty. I was able to get my arm lose and reach up and tap the door gunner to ask for a drink. He almost jumped out of the helicopter. He thought everybody was dead. He called out to the pilot, ‘there’s one still alive’.

“So I got to the evacuation hospital in Da Nang. I had face injuries. I was hit below the eye with shrapnel, and in the chest, cheek, and knee. They medi-vacced me to an army hospital in Colorado where facial/cranial surgeons worked on me. I was in hospital for close to five months and had four operations. The shrapnel hit my orbital and caused a catastrophic blow out, so they went in and put silver plates to hold my eye in. They did all the surgery from inside my mouth, so I couldn’t eat, and I had (medical) balloons up inside my sinuses.

“When I got out of there they sent me to another army unit in Colorado but I couldn’t take the inspections and the parades and the marching up and down. I couldn’t wait to get back to Vietnam where I understood things. I had been out of hospital two months when I went back.

“But my head wasn’t in a good place, although I didn’t know that at the time. And they didn’t know what was going on with me. So they sent me back up to the Cambodian border for a while and then I went back up north. When my time was up they let me go home. But the war really began for me when I left the army. I came back from Vietnam a different person to the one who went there.”

The father of three, who now believes he was exposed during the conflict to Agent Orange and its potentially deadly component dioxin, has been undergoing medical tests. Agent Orange was one of a range of herbicides used by the US to destroy forest cover and crops that protected and fed the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong during the war. It has been linked to several cancers and is reported to have already killed or maimed nearly 400,000 US soldiers and four million Vietnamese.

Today, Keaveney reveals he was recently tested for cancer and although so far free of the disease, dioxin was detected in his kidneys.

From his home in Las Vegas, his wife Raida, 50, at his side, he says: “I have just had tests. I don’t have cancer but I have dioxin on my kidneys. Dioxin is a foundation to Agent Orange and it’s a poison. It is killing Vietnam veterans. They sprayed it on the jungle and it went into the water. We drank the water.”

The couple will arrive in Scotland on Tuesday and have rented accommodation in Edinburgh, where their daughter Jaida, 29, is studying for a PhD, and intend to move here permanently.

Keaveney, who also has sons Dillon, 19, and John, 47, from a previous marriage, left the military in 1972 not realising he had what is now termed PTSD. He explains: “It wasn’t until later, when I got in trouble with the law, that they gave me a psychiatric evaluation and found out I had PTSD and a maximum case of it.”

During a brawl in a bar, he stabbed another man in the chest, was charged with attempted murder, and sentenced to nine years in jail but was released in just under five.

Then in 1981, he staged a hunger protest over inhumane treatment at a Veterans Association facility in LA. When an anguished fellow protester jumped from a roof to his death, Keaveney held army captain Shad Meshad hostage at knifepoint, with a SWAT team swooping in and drawing their guns on Keaveney. Charged with kidnapping, Keaveney recalls: “I was looking at life. I got on my knees and I prayed to God. If he would help me, I would help others. I’d like to say Jesus came down and opened the prison doors that night but it didn’t work that way.”

Instead, his victim dropped the case and Keaveney was placed on a New Directions pilot programme that was to get him back on his feet.

Later, when New Directions was in danger of folding, Keaveney stepped in, becoming its chief and raising millions of dollars to create hundreds of new homes to take homeless veterans off the streets.

The not-for-profit organisation also provided access to education, vocational training, drug and alcohol rehabilitation and family reunification, touching the lives of more than two million people overall. Looking back on his remarkable journey, Keaveney, whose work with veterans saw him travel to Russia and also Calcutta, at the request of Mother Teresa, says: “When I was told about the Presidential Citizens Medal I said, ‘there must be some kind of mistake, I’m an ex-felon.’ But they said, ‘no it is you’ and asked me to go to Washington DC with my family. How can a guy who comes from the streets of Bridgeton end up in the White House?”

Looking forward to arriving home after more than 50 years, Keaveney is ready for whatever comes: “I don’t fear death. The only thing I fear is God.

“If anything happens to me, I believe I am loved and whoever is left will be taken care of. I have had a great life. I love America, it is the greatest country in the world. Apart from Scotland.”

A war that left lasting legacy of loss and trauma

Long, costly, divisive and a defining conflict for the US, the Vietnam War left more than three million people dead.

Pitching North Vietnam against South Vietnam, the war, which became the focus of global geopolitical conflict, began in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia on November 1, 1955 and raged on until the fall of Saigon – the former capital of South Vietnam, now Ho Chi Minh City – on April 30, 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam and South Vietnam.

The conflict started when North Vietnam, which had defeated the French colonial administration of the country in 1954, wanted to unify the entire country under a single communist regime modelled on the then-Soviet Union and China. But the South Vietnamese government wanted to preserve a Vietnam more closely aligned with the West.

US military advisers, present in small numbers throughout the 1950s, were introduced on a large scale beginning in 1961, followed by active combat units in 1965. By 1969, more than 500,000 US military personnel were stationed in Vietnam.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union and China poured weapons, supplies and advisers into the North, which in turn provided support, political direction and regular combat troops for the campaign in the South.

But the burgeoning costs and casualties of the war became too much for the United States to bear. And opposition to the conflict in the US saw the country bitterly divided. It was a divide that remained even after then-President Richard Nixon signed the Paris Peace Accords and ordered the withdrawal of US military in 1973. Two years later in 1975 South Vietnam fell to a full-scale invasion by the North, becoming the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The final death toll? According to a 1995 official estimate by Vietnam, as many as two million civilians on both sides and 1.1 million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters. The US military has estimated that between 200,000 and 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died.

Meanwhile, US records show 58,220 US military fatalities.

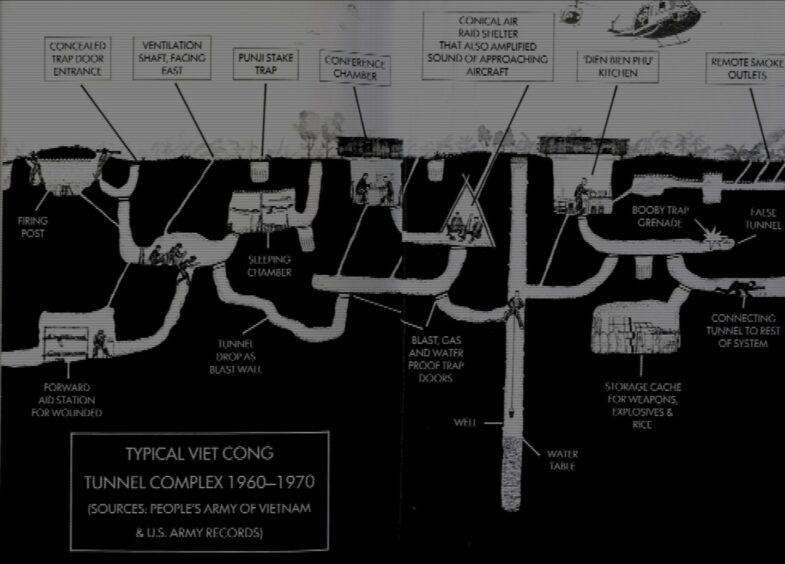

It needed a lot of moxie. You could blow yourself out of there in a heartbeat

The tunnel rats of the Vietnam War were small in number and stature but their courage, as they inched through pitch-black subterranean labyrinths, was immeasurable.

The National Museum of the United States Army dedicates a page to the rats on its website, concluding: “In a complicated war with a painful history in American culture, the courage, skill, and nerve of the tunnel rats shone as they invented a military skill in the midst of mortal danger.”

The tunnels, first discovered near Saigon in 1966, were usually so small only one soldier could enter at a time and, according to the National Museum, “most were short (most less than 5ft 5in) with a slight, wiry build. The job also required a special kind of mental toughness: crawling for hours in claustrophobic darkness expecting mortal danger could break down even the bravest men.

“The job also demanded lightning-quick reflexes and no hesitation: confrontations with venomous snakes or Viet Cong often occurred at hand-to-hand range.”

Thousands of underground tunnels and chambers criss-crossed Vietnam during the war, like those at Cu Chi beneath the then Saigon district and city (now Ho Chi Minh City) and at the Cambodian border as well as on the border between North and South Vietnam, known then as the DMZ (demilitarized zone) where Scots veteran John Keaveney operated. There were never more than 100 rats in Vietnam at one time with around 700 in total.

One US captain, Herbert Thornton, put together the volunteer teams trained to enter and clear the Viet Cong tunnels and said a tunnel rat “had to have an inquisitive mind, a lot of guts and a lot of real moxie…knowing what to touch and what not to touch to stay alive because you could blow yourself out of there in a heartbeat.”

Booby traps were common beneath ground and the rats could expect to face wired explosives, poisonous gas, stake pits, and tethered venomous snakes. Harold Roper, a tunnel rat in the early days of 1966, recalled: “I felt more fear than I’ve ever come close to feeling before or since.”

In their book, The Tunnels Of Cu Chi: A Remarkable Story Of War, authors Tom Mangold and John Penycate detail the subterranean war. Keaveney told The Sunday Post: “There were numerous tunnels around the DMZ in the mountains near Laos. If they were found then someone had to go in and inspect them.

“It couldn’t be some 6ft, 190lb soldier. It had to be some guy my height, short and on the slim side. This was a job that was done by volunteers. I believe there were 700 total volunteers from 1964 to 1973. Going into the tunnels you needed to be real careful, they were booby trapped. They were so big they had hospitals in them. For those ones we’d have to call airstrikes on them. My job was to go down and blow them up from within, just make them inoperable.”

In 1969, the tunnels were finally destroyed for good by B-52 carpet-bombing raids but not before they had already contributed significantly to the war.

Today some of these underground wartime warrens serve as tourist attractions for the many thousands of travellers who visit the country that was once South Vietnam.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© David Becker

© David Becker © Alamy Stock Photo

© Alamy Stock Photo © AP/Shutterstock

© AP/Shutterstock © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM